Bourbon Production Techniques

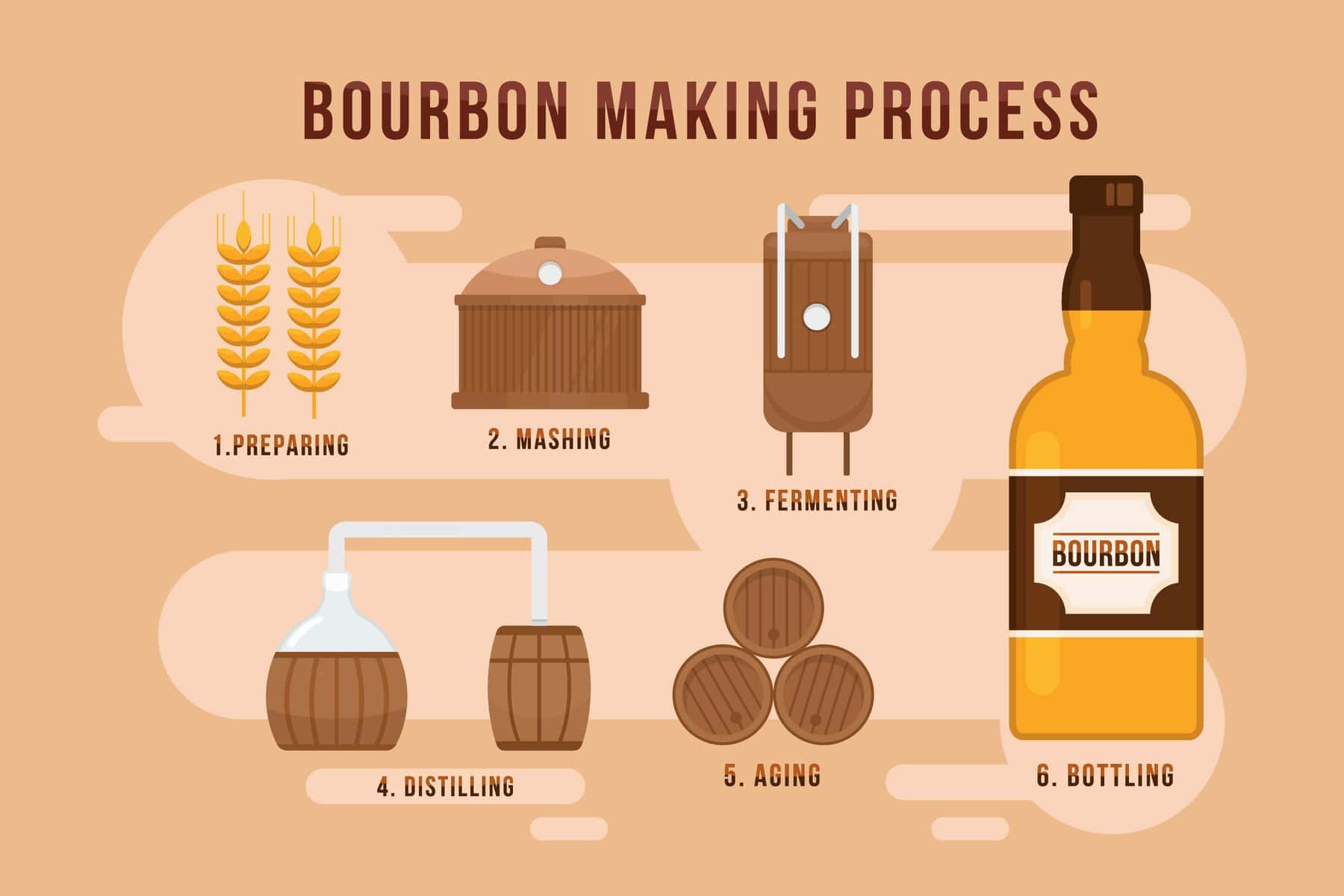

Bourbon, America’s native spirit, has a rich history and intricate production process that sets it apart from other whiskeys. From the selection of grains to the final aging process, every step contributes to its distinct flavor profile. Let’s delve into the fascinating world of bourbon production techniques and uncover what makes this iconic drink so special.

Fermentation Process

Yeast and Fermentation

The journey of bourbon begins with fermentation, a crucial step that sets the foundation for the spirit’s flavor. The fermentation process starts with the mash bill—a blend of grains, typically corn, rye, barley, and sometimes wheat. This mixture is cooked to convert starches into fermentable sugars. Once cooled, the mash is transferred to fermentation tanks.

Here, yeast comes into play. Yeast is a microorganism that converts sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide. The choice of yeast strain can significantly influence the flavor of the bourbon. Distilleries often use proprietary strains, some of which have been handed down through generations. The fermentation process usually lasts between three to seven days, during which the yeast works its magic, producing a “beer” or “wash” with an alcohol content of around 6-10%.

Fermentation temperature is also a critical factor. Warmer temperatures can speed up the process but may produce unwanted flavors, while cooler temperatures result in slower fermentation, allowing for more complex flavor development. The distiller’s skill lies in managing these variables to create a balanced and flavorful wash ready for distillation.

Grain Selection and Mashing

The specific grains used in the mash bill play a crucial role in determining the flavor profile of the final bourbon. Corn, which must constitute at least 51% of the mash bill to qualify as bourbon, imparts sweetness. Rye adds spiciness and complexity, while barley contributes a malty flavor and aids in fermentation. Some bourbons also include wheat, which can give a softer, smoother taste.

Once the grains are selected, they are ground into a coarse meal and mixed with water in a process known as mashing. The mixture is heated to convert the starches in the grains into fermentable sugars. This step is essential as it sets the stage for fermentation by providing the yeast with the necessary nutrients to produce alcohol.

Water Quality

Water is another key ingredient in bourbon production. The quality and mineral content of the water used can significantly impact the flavor of the final product. Kentucky, where many bourbons are produced, is renowned for its limestone-filtered water, which is high in calcium and magnesium. These minerals help to balance the pH of the mash and contribute to the overall flavor profile of the bourbon.

Distilleries often take great care in sourcing and testing their water to ensure it meets the required standards. Some even use water from specific springs or wells that have been used for generations, adding to the unique character of their bourbon.

Distillation Methods

Pot Still vs. Column Still

Once fermentation is complete, the wash undergoes distillation, a process that separates alcohol from the other components of the liquid. Distillation not only increases the alcohol content but also refines the flavor of the bourbon.

There are two primary types of stills used in bourbon production: pot stills and column stills. Each has its unique characteristics and impacts the final product differently.

- Pot Stills are the traditional choice for many small-batch and craft distilleries. They consist of a large, kettle-like vessel where the wash is heated. As the liquid boils, alcohol vapors rise and travel through a condenser, where they are cooled and collected. Pot stills usually require multiple distillation runs to achieve the desired alcohol concentration, which can enhance the complexity and depth of the bourbon’s flavor.

- Column Stills, on the other hand, are more modern and efficient. They consist of a tall column divided into sections or plates. As the wash enters the column, it is heated, and alcohol vapors rise through the plates. Each plate acts as a mini-distillation unit, allowing for continuous distillation. Column stills can produce higher-proof spirits in a single pass and are often used in large-scale production for their efficiency. However, some argue that they may produce a less complex flavor compared to pot stills.

Both distillation methods have their merits, and many distilleries use a combination of both to achieve a balance of efficiency and flavor complexity in their bourbon.

Distillation Process Details

In more detail, the distillation process begins by heating the fermented wash in the still. As the temperature rises, different compounds vaporize at different temperatures. The goal is to separate the alcohol from water and other components, capturing the desirable compounds while leaving behind impurities.

In a pot still, the first distillation run, known as the “stripping run,” produces a low-proof spirit called “low wine.” This is followed by a second distillation, or “spirit run,” which further purifies the alcohol and increases its proof. The distiller carefully monitors the temperature and cuts, separating the “heads” (initial portion, high in volatile compounds), “hearts” (middle portion, rich in ethanol and flavor compounds), and “tails” (final portion, containing heavier, less desirable compounds). Only the “hearts” are used for aging.

Column stills, being continuous, allow for a steady flow of wash and consistent separation of components. As the wash moves up the column, it encounters multiple plates where vapor and liquid phases interact. This repeated condensation and vaporization process efficiently separates ethanol from other compounds, producing a higher-proof distillate in one go. The distiller can adjust the reflux ratio, controlling the purity and flavor profile of the spirit.

Copper and Distillation

The material of the still, often copper, plays a significant role in the distillation process. Copper is highly effective at removing sulfur compounds from the wash, which can cause off-flavors. It also promotes beneficial chemical reactions that enhance the complexity and smoothness of the spirit. Copper stills are prized for these qualities, though they require regular maintenance to prevent wear and tear.

Barrel Aging

Types of Barrels

After distillation, the raw spirit, often referred to as “white dog,” is transferred into barrels for aging. The type of barrel used plays a significant role in shaping the final character of the bourbon.

Bourbon must be aged in new, charred oak barrels. The charring process involves burning the inside of the barrel, which creates a layer of charcoal. This charcoal acts as a natural filter, removing impurities and adding complexity to the spirit. The level of char can vary, typically from a light toast to a heavy char. A heavier char imparts more robust flavors, such as caramel, vanilla, and spice, while a lighter char allows more of the grain and distillation characteristics to shine through.

In addition to the level of char, the type of oak used is crucial. American white oak is the standard for bourbon barrels due to its porous nature, which allows the spirit to interact with the wood. This interaction extracts flavors and colors from the wood, contributing to the bourbon’s distinctive taste and amber hue.

Climate Impact

The climate in which the barrels are stored also impacts the aging process. Bourbon aging in Kentucky, for example, benefits from the state’s seasonal temperature fluctuations. During hot summers, the spirit expands and is absorbed into the wood, while in cooler winters, it contracts and is expelled from the wood. This cycle, known as “breathing,” accelerates the aging process and enhances the extraction of flavors from the barrel.

Warehouse conditions, such as location and design, further influence aging. Barrels stored in higher parts of the warehouse, known as the “sweet spot,” experience greater temperature variations, leading to more intense flavor development. Distilleries often rotate barrels to ensure even aging, though some prefer to leave them undisturbed to create unique variations within their product line.

Barrel Entry Proof

Another important factor in the aging process is the barrel entry proof—the alcohol content of the spirit when it is first placed in the barrel. By law, bourbon must be entered into the barrel at no more than 125 proof (62.5% alcohol by volume). Some distilleries choose to enter their bourbon at lower proofs, believing it allows for better extraction of flavors from the wood and a smoother final product. The interaction between the spirit and the wood over time gradually reduces the alcohol content, leading to a balanced and flavorful bourbon.

Aging Duration

The length of time bourbon spends aging in the barrel significantly impacts its flavor. While the minimum aging period for straight bourbon is two years, most bourbons are aged for at least four years, and some premium bourbons are aged for much longer. Extended aging allows the spirit to develop deeper, more complex flavors, but it also means that more of the bourbon evaporates over time—a phenomenon known as the “angel’s share.” Distillers must carefully balance aging time to achieve the desired flavor without losing too much product to evaporation.

Barrel Management

Effective barrel management is crucial for producing high-quality bourbon. This involves tracking each barrel’s age, location, and specific characteristics throughout the aging process. Some distilleries use sophisticated software to monitor these factors and make informed decisions about when to rotate barrels, sample the contents, or blend different batches to create a consistent product.

Blending is an art in itself, requiring a keen palate and extensive knowledge of the distillery’s inventory. Master distillers blend barrels of varying ages and flavor profiles to achieve the desired taste and quality for each batch of bourbon. This process ensures that each bottle of bourbon maintains the brand’s signature flavor while allowing for slight variations that add to its character.

Conclusion

Bourbon production is an art and a science, involving meticulous attention to detail at every step. From selecting the grains and managing the fermentation process to choosing the right distillation method and aging in carefully prepared barrels, each decision shapes the final product.

Understanding these techniques not only enhances appreciation for this beloved spirit but also highlights the craftsmanship that goes into every bottle. Whether you prefer a robust, spicy bourbon or a smoother, sweeter one, the journey from grain to glass is a testament to the skill and passion of bourbon makers.

FAQs

Disclosure: Our blog contains affiliate links to products. We may receive a commission for purchases made through these links. However, this does not impact our reviews and comparisons. We try our best to keep things fair and balanced, in order to help you make the best choice for you.